Dear Dr. Winestain,

Whilst I was at work the other day, mining vast amounts of data for a company that mines vast amounts of data, I drifted into my thoughts. I started pondering on the inevitable collapse of civilization - perhaps brought about by a human variant of TCA.

Imagine it: one by one, we all succumb to cork taint, developing a tragic inability to enjoy fine wines, until society crumbles under the weight of its own despair and we all smell of damp.

And yet, nature endures. If humanity were wiped from the face of the Earth, how long would it take for vines to conquer our cities? Would tendrils coil around abandoned skyscrapers like lonely, leafy serpents? Would vineyards return to their wild, unshackled form? Or is there some ancient wisdom to trellising that ensures vines must be tamed?

I suppose what I’m really asking is: why do we trellis vines at all? What did vineyards look like before we imposed our rigid systems upon them?

Dr. Winestain: Your inquiry - soaked as it is in existential dread and the acrid scent of hypothetical decay - touches on a most pressing issue: what becomes of the vine when the hand of man is no longer there to guide it?

To answer, we must first recognize the vine for what it is: an opportunist.

Vitis Vinifera, our beloved wine grape, is a natural-born scrambler. In the wild, it does not grow in neat, picturesque rows. It is a sneaky rogue, a blagard that slinks up trees, coils around rocks and ambushes structures, using anything it can grasp to ascend towards the sun.

Grapevines are natural climbers, historically sprawling along the ground or ascending trees in their quest for sunlight. They are climbers and schemers. If it was in your data mining office, it would be Jacob, the new Temp at the corner desk, with their beady eyes on your job like a jackal to the lamb.

Evidence suggests that as early as 10,000 years ago, humans began domesticating grapevines, initially allowing them to grow up trees. Over time, this practice evolved into more deliberate training systems.

About 2000 years ago, give or take a few decades, Roman agricultural writers like Columella and Pliny the Elder documented structured vineyard layouts. They described methods such as training vines up trees (Arbustum) and along stakes or trellises to improve yield and fruit quality.

During the medieval period, some European monks advanced viticulture by refining trellising techniques. They trained vines against walls, which retained heat and extended the growing season, influencing modern “espalier methods.”

Then came the Industrial Revolution and with it, agricultural research. This led to scientifically driven trellising systems.

Today, several systems dominate modern vineyards. I find it easiest to understand when compared to hairstyles and so should you.

Pergola System: The High Ponytail

Elegant, practical and effortlessly cool. Like a high ponytail lifting hair off the shoulders, pergola-trained vines are raised overhead, forming a canopy that shields grapes from sun and wind. Dating back to Rome and still favored in countries such as Spain, Italy and Argentina, this time-tested method maximizes space below—perfect for shade-loving crops or, if you prefer, a well-groomed beard.

Goblet & Bush Vine: The Pixie Cut

Short, strong, self-sufficient. Like a pixie cut that needs no styling, Goblet-trained vines stand alone, thriving without trellises. Dating back to the Greeks and Phoenicians, this ancient method, still common in Spain and the Rhône Valley, keeps vines low, conserving moisture and handling heat with effortless confidence. Simple, timeless and built to endure changing fashions.

Guyot System: The Classic Bob

Neat, structured, always in style. The Guyot system is a Bob. Precise and carefully maintained, with vines pruned and trained along wires for just the right balance of volume and control. Developed in France in the 1860s, it remains a go-to in Burgundy and Bordeaux, keeping vineyards looking sharp and producing at their best. B.O.B. - Burgundy or Bordeaux.

Vertical Shoot Positioning (VSP): The Sleek Blowout

Smooth, structured, flawlessly maintained. VSP-trained vines stand tall along trellis wires, ensuring perfect alignment, even sun exposure and optimal airflow. Popular in cooler climates like Oregon and New Zealand, this system keeps vineyards polished, productive and free of unruly tangles like glass hair.

Geneva Double Curtain: The Curtain Bangs

Layered, voluminous, perfectly balanced. The Geneva Double Curtain is the Curtain Bangs of Trellising. Splitting vines into two elegant sections, allows for better sun exposure and reduced shading. It was developed in the 1960s for high-yield vineyards in the USA and is both trendy and practical - giving vines (and hair) the perfect amount of structure and flair…so there.

Lyre System: The ‘90s Supermodel Blowout

Big, bold and built for maximum volume. Like a ‘90s supermodel blowout, the Lyre System lifts vines into two structured, upward-growing walls, ensuring full sun exposure and perfect airflow. Developed in the 1980s for premium vineyards, it’s all about high-impact structure - because when it comes to great wine (or great hair), more volume is always better.

But What Happens When We Are Gone?

Now, back to your pressing existential concern: a world abandoned by humankind, overrun by vines. Let’s look at this objectively…

1-3 years: With no pruning, domesticated grapevines would revert to their wilder, sprawling ways, sending shoots in every direction. Expect rooftops and balconies to start looking suspiciously vineyard-like.

5-10 years: Cities would begin to look like post-apocalyptic Tuscany. Vines would use power lines as makeshift trellises, creep into derelict shopping malls and transform overpasses into lush, wine-bearing tunnels.

50-100 years: Left unchecked, vines would swamp entire buildings. In warmer climates, some could produce grapes, leading to a haunting phenomenon: abandoned skyscrapers covered in fruit-laden vines, dripping with fermenting juice, while the wind carries the scent of forgotten vintages through empty streets.

200+ years: The vines would rule the Earth.

The Last Wine Critics

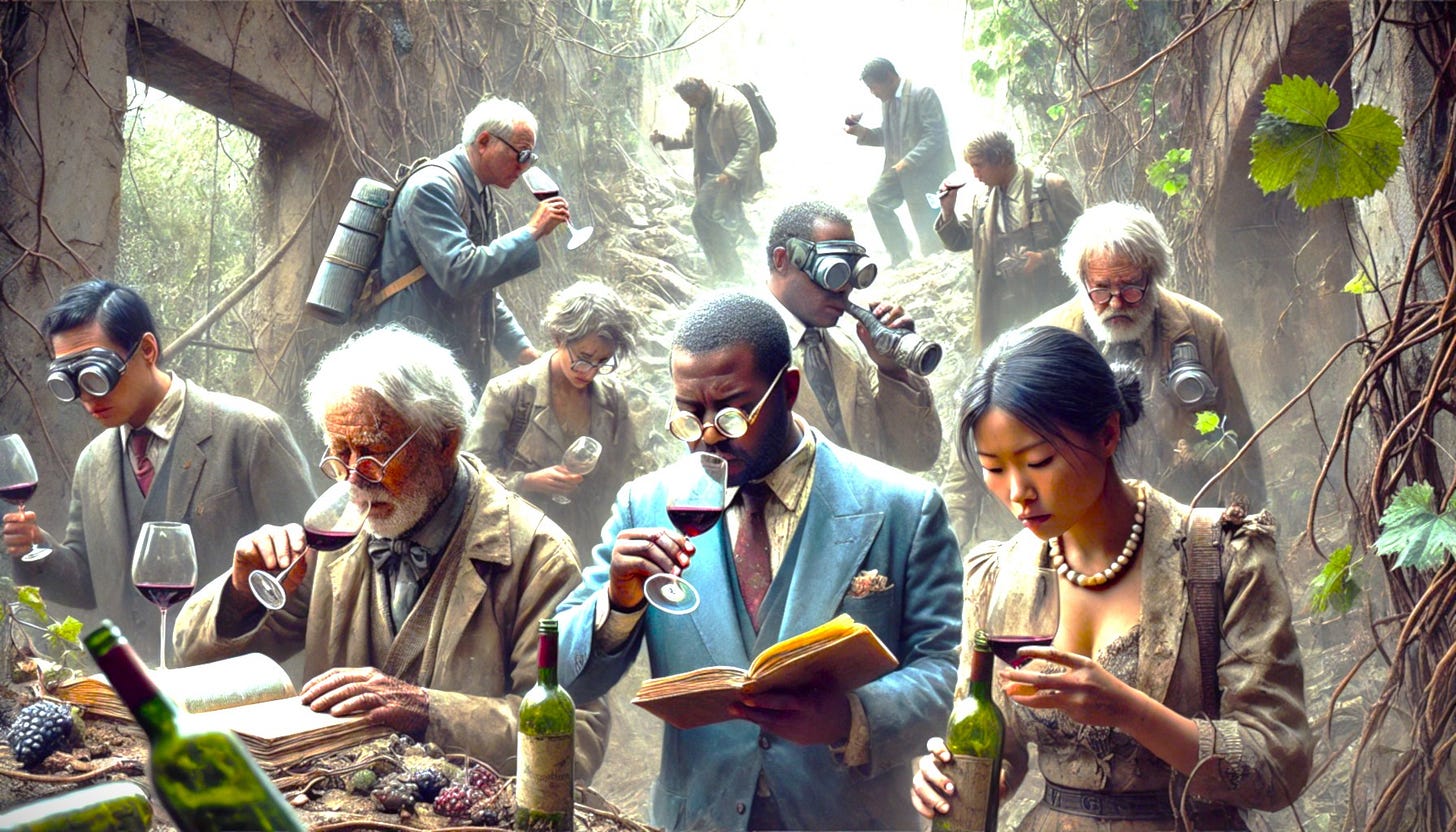

Yet, in this bleak and tangled world, a few brave souls persist - our last remaining wine critics.

Clad in tattered suits and scavenged eyewear, hunting in packs - technically, called “Pipes” they roam the vine-infested wastelands in search of bottles yet uncorked.

Armed with rusted corkscrews and notepads held together with duct tape, these nomadic connoisseurs infiltrate abandoned wine cellars, prying open century-old doors in hopes of finding a pre-apocalypse Bordeaux or a forgotten Champagne vault. For this is what they know how to do, oh and they do it very well.

Some trade in relics and rarities of the old world: a single-use Coravin mark 12, an unspoiled Indian Chenin Blanc Riedel glass, an 88-point Parker score scrawled onto a faded napkin. They brave mutant raccoons in the wreckage of Michelin-starred restaurants and navigate crumbling wine shops where bottles, long sealed away, have turned into either liquid gold or vinegar.

The grandest prize? A pristine bottle, intact and undisturbed, its label still legible. And yet, the tragedy persists - who will read their tasting notes? Only each other.

And then came The Vine People - the Emergence of Homo Vinea

Let us assume that radiation from an unexploded nuclear reactor in the Loire Valley mutates the vines. Over millennia, they evolve, growing humanoid offshoots with delicate tendrils for fingers. These creatures, initially slow-moving and sluggish from their high sugar content, begin fermenting their own bodily fluids, gaining sentience.

They worship a divine trellis and communicate in a complex language of rustling leaves and fermentation bubbles. Perhaps, in this far-flung future, the Vine People will raise a glass to their ancient benefactors - humanity - the species that, before its extinction, so wisely trellised the vine.